Perception and Social Media on Teens Statistics

Teens, Social Media, and Privacy

Teens share a wide range of data virtually themselves on social media sites;1 indeed the sites themselves are designed to encourage the sharing of data and the expansion of networks. However, few teens embrace a fully public approach to social media. Instead, they accept an array of steps to restrict and prune their profiles, and their patterns of reputation management on social media vary greatly according to their gender and network size. These are amongst the key findings from a new study based on a survey of 802 teens that examines teens' privacy direction on social media sites:

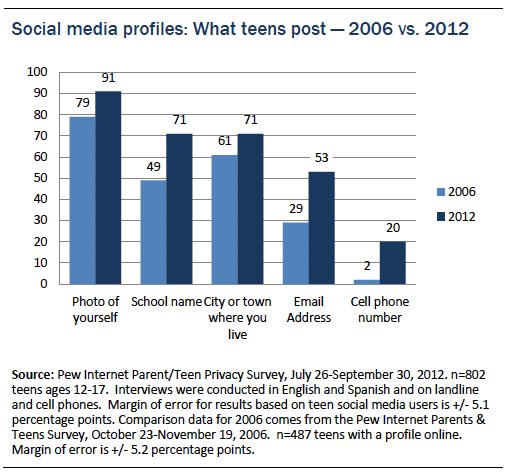

- Teens are sharing more information about themselves on social media sites than they did in the past. For the five different types of personal information that nosotros measured in both 2006 and 2012, each is significantly more probable to be shared by teen social media users in our most recent survey.

- Teen Twitter use has grown significantly: 24% of online teens use Twitter, up from sixteen% in 2011.

- The typical (median) teen Facebook user has 300 friends, while the typical teen Twitter user has 79 followers.

- Focus group discussions with teens show that they have waning enthusiasm for Facebook, disliking the increasing adult presence, people sharing excessively, and stressful "drama," but they keep using it because participation is an important part of overall teenage socializing.

- 60% of teen Facebook users go along their profiles individual, and virtually report high levels of conviction in their ability to manage their settings.

- Teens have other steps to shape their reputation, manage their networks, and mask information they don't want others to know; 74% of teen social media users take deleted people from their network or friends list.

- Teen social media users practice not express a high level of concern about third-party access to their data; merely 9% say they are "very" concerned.

- On Facebook, increasing network size goes hand in mitt with network variety, data sharing, and personal information management.

- In broad measures of online feel, teens are considerably more likely to report positive experiences than negative ones. For instance, 52% of online teens say they have had an experience online that made them experience skilful nearly themselves.

Teens are sharing more information about themselves on social media sites than they did in the past.

Teens are increasingly sharing personal information on social media sites, a trend that is likely driven past the development of the platforms teens employ as well as changing norms around sharing. A typical teen'due south MySpace profile from 2006 was quite dissimilar in class and office from the 2006 version of Facebook as well as the Facebook profiles that have become a hallmark of teenage life today. For the five different types of personal information that we measured in both 2006 and 2012, each is significantly more probable to be shared past teen social media users on the profile they employ nearly oftentimes.

- 91% post a photo of themselves, upward from 79% in 2006.

- 71% mail service their school name, up from 49%.

- 71% post the city or boondocks where they live, upwards from 61%.

- 53% post their email address, upward from 29%.

- xx% post their cell phone number, upwards from 2%.

In addition to the trend questions, nosotros also asked five new questions virtually the profile teens use almost often and found that amidst teen social media users:

- 92% postal service their real proper noun to the contour they use nearly oft.2

- 84% post their interests, such as movies, music, or books they like.

- 82% postal service their nascency date.

- 62% post their human relationship status.

- 24% post videos of themselves.

Older teens are more than likely than younger teens to share certain types of information, simply boys and girls tend to postal service the same kind of content.

Generally speaking, older teen social media users (ages 14-17), are more than likely to share certain types of data on the profile they use most frequently when compared with younger teens (ages 12-13).

Older teens who are social media users more than oftentimes share:

- Photos of themselves on their profile (94% older teens vs. 82% of younger teens)

- Their schoolhouse name (76% vs. 56%)

- Their relationship status (66% vs. l%)

- Their cell telephone number (23% vs. eleven%)

While boys and girls generally share personal information on social media profiles at the aforementioned rates, cell phone numbers are a primal exception. Boys are significantly more likely to share their numbers than girls (26% vs. 14%). This is a departure that is driven by older boys. Various differences between white and African-American social media-using teens are also significant, with the nigh notable being the lower likelihood that African-American teens volition disembalm their real names on a social media profile (95% of white social media-using teens practise this vs. 77% of African-American teens).3

16% of teen social media users have set their profile to automatically include their location in posts.

Beyond basic profile information, some teens choose to enable the automatic inclusion of location information when they mail. Some xvi% of teen social media users said they ready upwards their profile or account so that information technology automatically includes their location in posts. Boys and girls and teens of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds are equally likely to say that they have set up up their profile to include their location when they mail service. Focus group data suggests that many teens find sharing their location unnecessary and unsafe, while others appreciate the opportunity to bespeak their location to friends and parents.

Teen Twitter utilize has grown significantly: 24% of online teens apply Twitter, up from sixteen% in 2011.

Twitter draws a far smaller crowd than Facebook for teens, but its use is rising. One in four online teens uses Twitter in some fashion. While overall utilize of social networking sites among teens has hovered around 80%, Twitter grew in popularity; 24% of online teens apply Twitter, upwardly from 16% in 2011 and 8% the first time nosotros asked this question in tardily 2009.

African-American teens are substantially more likely to report using Twitter when compared with white youth.

Standing a design established early in the life of Twitter, African-American teens who are internet users are more likely to use the site when compared with their white counterparts. Two in five (39%) African-American teens utilize Twitter, while 23% of white teens use the service.

Public accounts are the norm for teen Twitter users.

While those with Facebook profiles almost often choose private settings, Twitter users, by contrast, are much more than probable to have a public account.

- 64% of teens with Twitter accounts say that their tweets are public, while 24% say their tweets are private.

- 12% of teens with Twitter accounts say that they "don't know" if their tweets are public or private.

- While boys and girls are every bit probable to say their accounts are public, boys are significantly more likely than girls to say that they don't know (21% of boys who take Twitter accounts study this, compared with 5% of girls).

The typical (median) teen Facebook user has 300 friends, while the typical teen Twitter user has 79 followers.

Overall, teens have far fewer followers on Twitter when compared with Facebook friends; the typical (median) teen Facebook user has 300 friends, while the typical (median) teen Twitter user has 79 followers. Girls and older teens tend to have substantially larger Facebook friend networks compared with boys and younger teens.

Teens' Facebook friendship networks largely mirror their offline networks. Seven in ten say they are friends with their parents on Facebook.

Teens, like other Facebook users, have different kinds of people in their online social networks. And how teens construct that network has implications for who can come across the material they share in those digital social spaces:

- 98% of Facebook-using teens are friends with people they know from school.

- 91% of teen Facebook users are friends with members of their extended family.

- 89% are connected to friends who do not attend the same school.

- 76% are Facebook friends with brothers and sisters.

- 70% are Facebook friends with their parents.

- 33% are Facebook friends with other people they have not met in person.

- thirty% accept teachers or coaches as friends in their network.

- 30% have celebrities, musicians or athletes in their network.

Older teens tend to be Facebook friends with a larger diversity of people, while younger teens are less likely to friend certain groups, including those they have never met in person.

Older teens are more likely than younger ones to have created broader friend networks on Facebook. Older teens (14-17) who use Facebook are more likely than younger teens (12-thirteen) to be continued with:

- Friends who go to different schools (92% vs. 82%)

- People they accept never met in person, not including celebrities (36% vs. 25%)

- Teachers or coaches (34% vs. 19%)

Girls are besides more likely than boys (37% vs. 23%) to be Facebook friends with coaches or teachers, the simply category of Facebook friends where boys and girls differ.

African-American youth are nigh twice every bit likely equally whites to be Facebook friends with celebrities, athletes, or musicians (48% vs. 25%).

Focus group discussions with teens show that they take waning enthusiasm for Facebook.

In focus groups, many teens expressed waning enthusiasm for Facebook. They dislike the increasing number of adults on the site, get annoyed when their Facebook friends share inane details, and are drained by the "drama" that they described as happening frequently on the site. The stress of needing to manage their reputation on Facebook too contributes to the lack of enthusiasm. Nonetheless, the site is still where a large amount of socializing takes place, and teens feel they need to stay on Facebook in social club to not miss out.

Users of sites other than Facebook express greater enthusiasm for their option.

Those teens who used sites like Twitter and Instagram reported feeling like they could amend express themselves on these platforms, where they felt freed from the social expectations and constraints of Facebook. Some teens may migrate their activeness and attending to other sites to escape the drama and pressures they find on Facebook, although almost nonetheless remain active on Facebook as well.

60% of teen Facebook users keep their profiles individual, and most written report high levels of confidence in their ability to manage their settings.

Teens have a multifariousness of ways to make available or limit access to their personal information on social media sites. Privacy settings are one of many tools in a teen's personal data management arsenal. Among teen Facebook users, most choose private settings that permit only approved friends to view the content that they post.

Most keep their Facebook profile private. Girls are more likely than boys to restrict access to their profiles.

Some threescore% of teens ages 12-17 who utilize Facebook say they accept their contour set to individual, and then that only their friends tin see information technology. Another 25% have a partially private profile, fix then that friends of their friends can run into what they post. And fourteen% of teens say that their profile is completely public.4

- Girls who use Facebook are substantially more than probable than boys to have a individual (friends just) profile (lxx% vs. l%).

- By dissimilarity, boys are more likely than girls to accept a fully public profile that everyone can see (20% vs. viii%).

Most teens express a loftier level of confidence in managing their Facebook privacy settings.

More than than one-half (56%) of teen Facebook users say information technology'southward "not difficult at all" to manage the privacy controls on their Facebook contour, while 1 in three (33%) say information technology's "non also difficult." Just 8% of teen Facebook users say that managing their privacy controls is "somewhat difficult," while less than i% describe the process as "very hard."

Teens' feelings of efficacy increase with age:

- 41% of Facebook users ages 12-thirteen say it is "non difficult at all" to manage their privacy controls, compared with 61% of users ages 14-17.

- Boys and girls written report similar levels of confidence in managing the privacy controls on their Facebook profile.

For most teen Facebook users, all friends and parents run into the same information and updates on their profile.

Beyond general privacy settings, teen Facebook users have the option to place further limits on who tin can come across the data and updates they post. However, few choose to customize in that way: Among teens who have a Facebook account, only eighteen% say that they limit what certain friends tin can come across on their contour. The vast bulk (81%) say that all of their friends see the aforementioned thing on their profile.5 This arroyo also extends to parents; only 5% of teen Facebook users say they limit what their parents can see.

Teens take other steps to shape their reputation, manage their networks, and mask information they don't desire others to know; 74% of teen social media users have deleted people from their network or friends list.

Teens are cognizant of their online reputations, and take steps to curate the content and appearance of their social media presence. For many teens who were interviewed in focus groups for this report, Facebook was seen as an extension of offline interactions and the social negotiation and maneuvering inherent to teenage life. "Likes" specifically seem to exist a strong proxy for social status, such that teen Facebook users will manipulate their profile and timeline content in order to garner the maximum number of "likes," and remove photos with as well few "likes."

Pruning and revising profile content is an important part of teens' online identity direction.

Teen direction of their profiles tin take a multifariousness of forms – we asked teen social media users almost five specific activities that chronicle to the content they mail and establish that:

- 59% take deleted or edited something that they posted in the by.

- 53% have deleted comments from others on their profile or business relationship.

- 45% have removed their name from photos that have been tagged to identify them.

- 31% take deleted or deactivated an entire contour or account.

- 19% have posted updates, comments, photos, or videos that they later regretted sharing.

74% of teen social media users have deleted people from their network or friends' list; 58% have blocked people on social media sites.

Given the size and composition of teens' networks, friend curation is also an integral part of privacy and reputation management for social media-using teens. The practice of friending, unfriending, and blocking serve every bit privacy management techniques for controlling who sees what and when. Amidst teen social media users:

- Girls are more likely than boys to delete friends from their network (82% vs. 66%) and cake people (67% vs. 48%).

- Unfriending and blocking are equally common among teens of all ages and across all socioeconomic groups.

58% of teen social media users say they share inside jokes or cloak their messages in some way.

As a mode of creating a different sort of privacy, many teen social media users will obscure some of their updates and posts, sharing within jokes and other coded messages that but certain friends will understand:

- 58% of teen social media users say they share within jokes or cloak their messages in some way.

- Older teens are considerably more likely than younger teens to say that they share inside jokes and coded messages that only some of their friends empathize (62% vs. 46%).

26% say that they mail simulated data like a simulated name, age, or location to help protect their privacy.

One in iv (26%) teen social media users say that they post simulated data similar a false proper name, historic period or location to help protect their privacy.

- African-American teens who use social media are more likely than white teens to say that they post fake data to their profiles (39% vs. 21%).

Teen social media users do not limited a high level of concern about third-party access to their data; simply 9% say they are "very" concerned.

Overall, 40% of teen social media users say they are "very" or "somewhat" concerned that some of the information they share on social networking sites might exist accessed by third parties similar advertisers or businesses without their cognition. Withal, few report a loftier level of business organization; 31% say that they are "somewhat" concerned, while merely 9% say that they are "very" concerned.half dozen Another 60% in total study that they are "not too" concerned (38%) or "not at all" concerned (22%).

- Younger teen social media users (12-13) are considerably more likely than older teens (14-17) to say that they are "very concerned" about third political party access to the information they share (17% vs. six%).

Insights from our focus groups suggest that some teens may not accept a adept sense of whether the data they share on a social media site is being used by 3rd parties.

When asked whether they thought Facebook gives anyone else access to the information they share, one eye schooler wrote: "Anyone who isn't friends with me cannot meet anything about my profile except my name and gender. I don't believe that [Facebook] would do anything with my info." Other loftier schoolers shared similar sentiments, assertive that Facebook would not or should non share their data.

Parents, by contrast, limited high levels of business organization near how much data advertisers can learn about their children'due south behavior online.

Parents of the surveyed teens were asked a related question: "How concerned are you about how much data advertisers can learn about your child's online beliefs?" A full 81% of parents written report being "very" or "somewhat" concerned, with 46% reporting they are "very concerned." Just 19% written report that they are not too concerned or not at all concerned about how much advertisers could larn about their child's online activities.

Teens who are concerned about tertiary party access to their personal information are also more probable to engage in online reputation direction.

Teens who are somewhat or very concerned that some of the information they share on social network sites might be accessed by third parties similar advertisers or businesses without their noesis more frequently delete comments, untag themselves from photos or content, and deactivate or delete their entire account. Among teen social media users, those who are "very" or "somewhat" concerned about third party access are more probable than less concerned teens to:

- Delete comments that others have made on their contour (61% vs. 49%).

- Untag themselves in photos (52% vs. 41%).

- Delete or deactivate their profile or account (38% vs. 25%).

- Post updates, comments, photos or videos that they later regret (26% vs. 14%).

On Facebook, increasing network size goes mitt in hand with network variety, information sharing, and personal information management.

Teens with larger Facebook networks are more than frequent users of social networking sites and tend to have a greater variety of people in their friend networks. They likewise share a wider range of information on their profile when compared with those who have a smaller number of friends on the site. Yet fifty-fifty every bit they share more than information with a wider range of people, they are also more actively engaged in maintaining their online profile or persona.

Teens with large Facebook friend networks are more frequent social media users and participate on a wider diversity of platforms in addition to Facebook.

Teens with larger Facebook networks are fervent social media users who exhibit a greater tendency to "diversify" their platform portfolio:

- 65% of teens with more than 600 friends on Facebook say that they visit social networking sites several times a mean solar day, compared with 27% of teens with 150 or fewer Facebook friends.

- Teens with more than 600 Facebook friends are more than three times as likely to also have a Twitter business relationship when compared with those who accept 150 or fewer Facebook friends (46% vs. 13%). They are six times equally likely to use Instagram (12% vs. 2%).

Teens with larger Facebook networks tend to have more than multifariousness within those networks.

Virtually all Facebook users (regardless of network size) are friends with their schoolmates and extended family unit members. However, other types of people begin to appear as the size of teens' Facebook networks aggrandize:

- Teen Facebook users with more than than 600 friends in their network are much more likely than those with smaller networks to exist Facebook friends with peers who don't attend their ain school, with people they have never met in person (not including celebrities and other "public figures"), as well every bit with teachers or coaches.

- On the other manus, teens with the largest friend networks are actually less likely to be friends with their parents on Facebook when compared with those with the smallest networks (79% vs. 60%).

Teens with large networks share a wider range of content, just are too more active in profile pruning and reputation management activities.

Teens with the largest networks (more 600 friends) are more likely to include a photo of themselves, their school proper noun, their relationship status, and their jail cell phone number on their contour when compared with teens who have a relatively small-scale number of friends in their network (under 150 friends). Withal, teens with large friend networks are also more active reputation managers on social media.

- Teens with larger friend networks are more than likely than those with smaller networks to block other users, to delete people from their friend network entirely, to untag photos of themselves, or to delete comments others have made on their contour.

- They are also essentially more likely to automatically include their location in updates and share within jokes or coded messages with others.

In wide measures of online experience, teens are considerably more likely to report positive experiences than negative ones.

In the current survey, nosotros wanted to understand the broader context of teens' online lives beyond Facebook and Twitter. A majority of teens study positive experiences online, such as making friends and feeling closer to some other person, just some do run into unwanted content and contact from others.

- 52% of online teens say they have had an experience online that fabricated them feel skilful nearly themselves. Among teen social media users, 57% said they had an feel online that fabricated them experience good, compared with 30% of teen net users who practice not employ social media.

- I in iii online teens (33%) say they take had an feel online that made them feel closer to another person. Looking at teen social media users, 37% report having an experience somewhere online that made them experience closer to another person, compared with just 16% of online teens who do not utilize social media.

One in half dozen online teens say they have been contacted online by someone they did not know in a way that fabricated them feel scared or uncomfortable.

Unwanted contact from strangers is relatively uncommon, just 17% of online teens report some kind of contact that fabricated them experience scared or uncomfortable.7 Online girls are more than than twice as probable as boys to report contact from someone they did not know that made them feel scared or uncomfortable (24% vs. 10%).

Few internet-using teens have posted something online that caused problems for them or a family unit fellow member, or got them in trouble at schoolhouse.

A small-scale percentage of teens have engaged in online activities that had negative repercussions for them or their family; four% of online teens say they take shared sensitive information online that later caused a problem for themselves or other members of their family unit. Another 4% take posted information online that got them in trouble at school.

More half of internet-using teens have decided not to postal service content online over reputation concerns.

More than one-half of online teens (57%) say they have decided non to post something online because they were concerned it would reflect badly on them in the future. Teen social media users are more likely than other online teens who do non use social media to say they take refrained from sharing content due to reputation concerns (61% vs. 39%).

Large numbers of youth have lied nigh their historic period in order to proceeds access to websites and online accounts.

In 2011, we reported that close to one-half of online teens (44%) admitted to lying most their age at one time or another so they could access a website or sign upwardly for an online account. In the latest survey, 39% of online teens admitted to falsifying their historic period in club gain access to a website or account, a finding that is not significantly different from the previous survey.

Shut to one in iii online teens say they accept received online advertisement that was conspicuously inappropriate for their age.

Exposure to inappropriate advertising online is one of the many risks that parents, youth advocates, and policy makers are concerned most. Yet, little has been known until now about how often teens see online ads that they experience are intended for more (or less) mature audiences. In the latest survey, 30% of online teens say they have received online advert that is "clearly inappropriate" for their age.

About the survey and focus groups

These findings are based on a nationally representative phone survey run by the Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project of 802 parents and their 802 teens ages 12-17. It was conducted between July 26 and September 30, 2012. Interviews were conducted in English and Castilian and on landline and jail cell phones. The margin of error for the full sample is ± 4.5 percent points.

This study marries that data with insights and quotes from in-person focus groups conducted by the Youth and Media team at the Berkman Middle for Internet & Society at Harvard University starting time in February 2013. The focus groups focused on privacy and digital media, with special accent on social media sites. The team conducted 24 focus group interviews with 156 students across the greater Boston area, Los Angeles (California), Santa Barbara (California), and Greensboro (Northward Carolina). Each focus group lasted 90 minutes, including a xv-minute questionnaire completed prior to starting the interview, consisting of 20 multiple-choice questions and 1 open-ended response. Although the research sample was not designed to plant representative cantankerous-sections of item population(s), the sample includes participants from diverse ethnic, racial, and economic backgrounds. Participants ranged in historic period from 11 to 19. The hateful age of participants is fourteen.5.

In improver, 2 online focus groups of teenagers ages 12-17 were conducted past the Pew Internet Project from June 20-27, 2012 to help inform the survey pattern. The first focus grouping was with 11 eye schoolers ages 12-14, and the second group was with 9 high schoolers ages 14-17. Each group was mixed gender, with some racial, socio-economical, and regional diversity. The groups were conducted as an asynchronous threaded word over three days using an online platform and the participants were asked to log in twice per day.

Throughout this study, this focus grouping material is highlighted in several ways. Pew's online focus group quotes are interspersed with relevant statistics from the survey in order to illustrate findings that were echoed in the focus groups or to provide boosted context to the information. In addition, at several points, there are extensive excerpts boxed off equally standalone text boxes that elaborate on a number of of import themes that emerged from the in-person focus groups conducted past the Berkman Center.

0 Response to "Perception and Social Media on Teens Statistics"

Post a Comment